It’s been said that “the Jews are a People of the Book,”1 and I’m not inclined to argue. I know it’s talking about the Torah—and the fact that, in forbidding graphic representations of the Divine, most of our religious-creative expression has taken the form of writing—but it hits home on a more personal level, too. I’ve always been a voracious reader, tearing through summer reading lists from my school and local library and defying my parents’ attempts to impose a bedtime by staying up reading until I fell asleep with my book still open. If my dad came in to chide me about the light, I’d turn it off and read in the dark. I slept in a bunkbed with only a tiny shelf for a bedside table, and so my books slept with me in piles on the mattress (15-20 at a time).

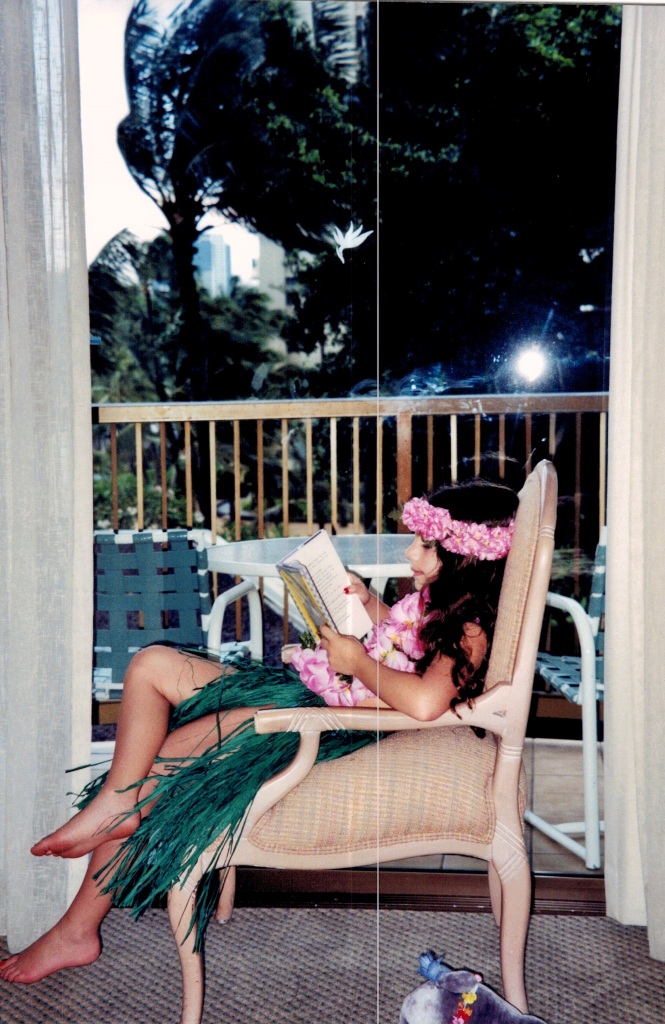

Here I am at the age of six, on vacation in Hawaii, spending my afternoon… reading. Sources inform me that the book in question is Junie B., First Grader (At Last!). | Courtesy of Robin Kohn © 2002

I didn’t decide that I wanted to write a book until I was ten. My friend Hannah approached me with the handwritten first page of her novel and invited me to write it with her. From our first collaborative writing session—we alternated typing and dictating—I was hooked. It was about a girl named Nalith who was half-dragon, and we wrote about 70 pages in three years before we finally lost interest. I started about a dozen more stories in the next decade, but not once did I reach the end.

It was about that same time—the end of eighth grade—that I last celebrated Simchat Torah, the holiday I best remember for the way our entire school would gather in the synagogue to unroll the torah scroll. It was so long, it took over a hundred students, parents, and teachers to hold the whole thing as it wrapped around the edge of the sanctuary. One lucky student got to read the final line of Devarim (Deuteronomy) and one got to read the first line of Bereishit (Genesis). In eighth grade, it was me. I can still remember the nervous excitement I felt as I bent in front of the scroll to read: Bereishit bara Elohim et ha-shamaim v’et ha-aretz. “In the beginning, the Lord created the heavens and the earth…”

I wish I could say it struck me as symbolic, then—this ritual of ending in order to begin again. But I was thirteen and just excited to show off. There was nothing particularly profound to me about endings. In the years since, though, as I’ve started story after story after story, it’s started to dawn on me how rare and special endings really are.

Two-and-a-half years ago, I started an MFA program with one goal: I wanted to finish a novel. I didn’t care how good it was, I just wanted to finally—after nearly twelve years—type the end. Okay, that’s a lie. I’m a perfectionist and did very much care how good it was. But the point remains that finishing—coming to an end—had become a prospect so deeply intimidating that I doubted whether I could do it on my own. Starting a program with mentorship, deadlines, and consequences felt like a great way to face that fear, one way or the other.

Eighteen years later, not much had changed. This is Florida, though, not Hawaii, and I’m reading Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Calculating Stars. | Courtesy of Mark Scaggs © 2020

Still, finishing a novel felt like a far-off dream when I first started. I could write and write without thinking about stopping, and between the pandemic and several cross-country moves, the past two years vanished almost in the blink of an eye. And so it came almost as a surprise when, last Tuesday night, as the sun set and Simchat Torah began, I sent off the final draft of my novel to my mentors.

Now that I’m no longer thirteen, I can appreciate how deeply profound it felt to reach the end of my own book at the same time as we began the celebration of the ending of our most important Book. For the first time in twelve years, I’ve truly felt the power of what it means to reach an ending and how it feels to pause, take a breath, and dive right back in again.

The next morning, I sat down at my computer and set to work on my next book. My thesis novel is far from perfect (and I’m sure I’ll revisit it many more times as it makes its way into the hands of agents and, hopefully, publishers), but for now, it’s a new cycle and a new story. I have new characters and a new setting, new questions and new hurtles. Yet so much recurs, too. The love that I have for Jewish folklore hasn’t changed, nor has my passion for Jewish history, Jewish culture, and Jewish stories. And so I finish one story in order to begin again—only this time, I’m a bit more sure I know how I want it to end.

My very sweet partner bought me this carrot cake to celebrate turning in my thesis novel. Why is there a first birthday candle on it? I asked the same question. | Image © Rebecca Glazer 2021

1Others have probably said it, too, but these words belong to Geoffrey Hartman in “On the Jewish Imagination,” published in the September 1985 edition of Prooftexts via the Indiana University Press. If you can get your hands on a copy, I highly recommend it. It gave me a lot of thoughts, which hopefully I’ll share in a future post.

Nice

LikeLike

It’s an awesome feeling, isn’t it? Finally completing something that you never thought was possible? I enjoyed your take on the process. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed it! Thanks so much for reading.

LikeLike